I get it – sometimes, it feels easier to roll out of bed and exercise immediately without eating anything beforehand. Many of the runners I’ve worked with (myself included) have fallen into the trap of running in a fasted state some or all of the time. However, just because you can run fasted doesn’t mean you should!

In this article, I’ll explore the pros and cons of running fasted and how to determine whether this nutrition strategy is appropriate for you.

Please note that I am an affiliate for some of the products I’ve linked to in this post. If you click the link here and make a purchase, I may earn a commission at no extra cost to you.

If you do a Google search on “what is fasted running?” you’ll quickly find that there are many proposed definitions. Some people defined fasted running as simply running “on an empty stomach” without mentioning how many hours after eating this might be. Others define fasted running as running after 4-12 hours of no eating, while others say it means running 10-14 hours after eating.

There’s no consensus on what it means to run in a fasted state. Some say exercising after forgoing food for as little as 4 hours is fasted exercise; others say 12 hours is the cutoff. I define fasted running as running after having consumed no food for 10 or more hours. For most people, this typically takes the form of running after fasting overnight during sleep.

When you run after fasting for 10-12 hours, this means you’ll be starting your run with low muscle and/or liver glycogen stores. Glycogen is the storage form of glucose, which your body mobilizes to create energy while exercising and fasting.

When you run in a fasted state, your body has less glycogen (and thus less glucose) available to fuel the activity. Instead, it must tap into your body’s fat stores to create cellular energy. Fat can be converted into cellular energy through fatty acid β-oxidation and ketone synthesis.

For some runners, the physiological effect of fasted running – increased fat burning – is the main reason they engage in this practice. However, other people slip into the routine of fasted running for gastrointestinal or time reasons.

Next, let’s discuss the reasons why active individuals may choose to run in a fasted state.

Fasted running is growing in popularity, for better or for worse. Here are the most common reasons why runners tell me they run in a fasted state:

Is running fasted really the best solution to the concerns cited above? It depends. Let’s discuss why…

There are many vocal proponents of “fasted cardio” (fasted running is a form of fasted cardio) to promote body fat loss. I can understand why this approach may sound appealing; after all, nearly 1 in 3 adults are overweight, and 2 in 5 adults in the U.S. are obese. (Source)

As appealing as it might sound, I have not found fasted running beneficial for body fat loss.

This may be because fasted running primarily causes you to tap into intramuscular fat (fat residing inside your muscles) for fuel; fasted exercise can tap into “peripheral fat” i.e., subcutaneous fat or the fat you see in the mirror. However, the reliance on peripheral fat for energy during endurance exercise like running is likely to be less than the reliance on intramuscular fat.

Of course, there are those individuals out there who will say that fasted running helped them lose body fat. However, this is more likely because fasted running puts them into a calorie deficit, leading to body fat loss, rather than the effects of fasted running itself.

There is a growing interest among athletes in becoming “fat-adapted.” It is a laudable goal to want to become fat-adapted, especially in a society where most people are chronic sugar-burners, heavily reliant on glucose for fuel as a result of their high-carbohydrate diets.

Proponents of fasted running for fat adaptation claim it will allow you to run longer while maintaining or improving your performance, improving blood sugar control, balancing your mood, and boosting your recovery.

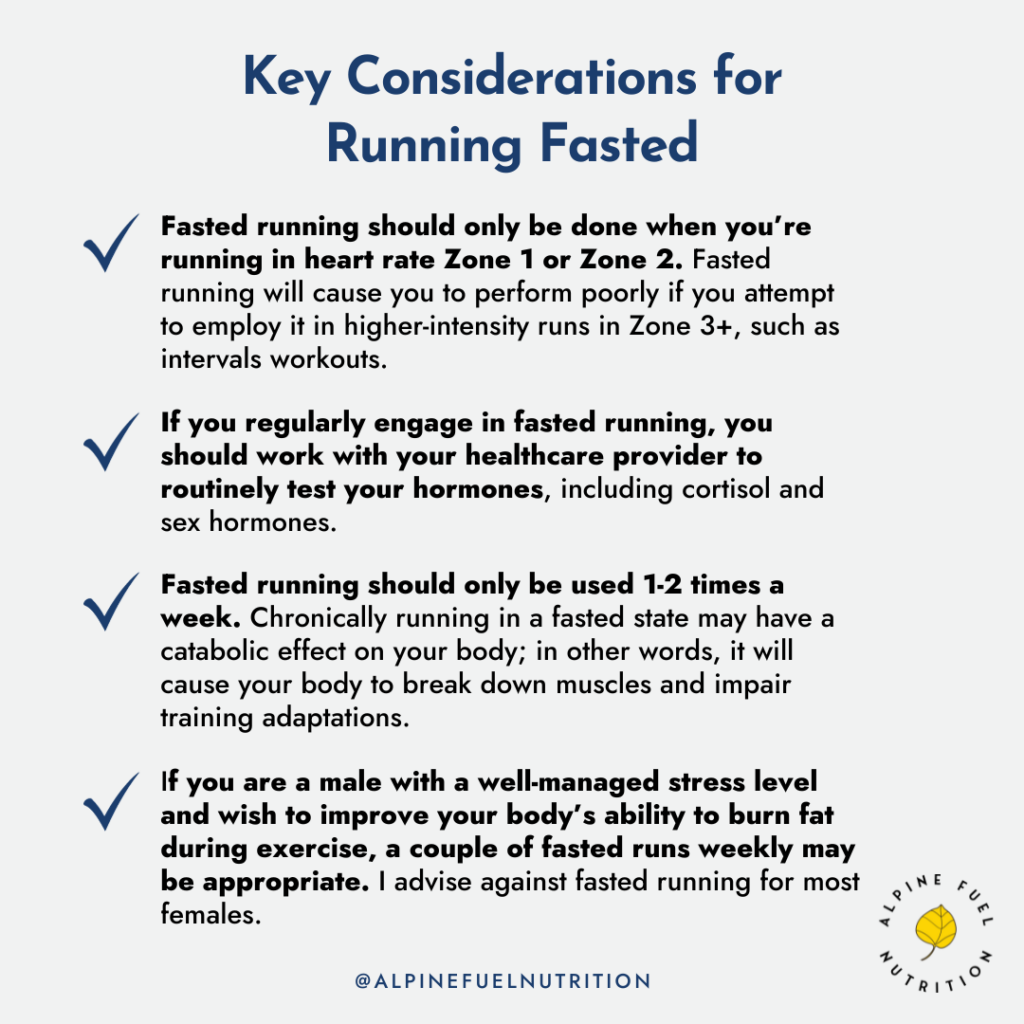

As a sports nutritionist and runner, I think strategically incorporating fasted running to promote fat adaptation can benefit certain athletes during training. However, it is NOT a cure-all for your running and health woes; it is one potential tool in a runner’s nutrition toolbox.

Furthermore, what you eat as a runner is even more critical for promoting fat adaptation than running fasted. If you are a trail runner, check out my blog on trail running nutrition foundations to learn how to eat to promote metabolic health and fat adaptation.

Many runners tell me they accidentally fell into the habit of running in a fasted state because they experience gastrointestinal (GI) distress if they eat before their run.

If you consistently run in a fasted state because your GI system rejects food consumed pre-run, you need to figure out why you’re not digesting well pre-run rather than continue to perform fasted training indefinitely. For example, you may be eating the wrong combination of foods or have inadequate time between eating and running.

A sports nutritionist can help you figure out how to optimize your nutrition so you can have a happy gut while running and in your daily life!

I can’t tell you how many runners tell me they don’t have time to eat before their runs.

While I understand that many people have busy, tight schedules, this is not a good reason to implement fasted running, especially if your busy schedule leads you to fast before every run.

Instead, we need to figure out why you lack time to nourish your body before running and strategize ways to get food into your body. For example, if you like to run first thing in the morning, you may need to wake up a bit earlier to create time to eat before training. If you don’t have time (at least an hour) to eat breakfast before running, you’ll need to figure out a small snack you can eat before your run.

There are a handful of potential benefits of running fasted. It is important to note that much of the research on fasted exercise has been performed in men, not women; therefore, it is difficult to extrapolate this research to female athletes.

I see many athletes in my nutrition practice who are metabolically unhealthy despite their physical activity level. You cannot exercise your way out of an unhealthy diet!

What do I mean by “metabolically unhealthy?” A metabolically unhealthy individual is someone who has some combination of metabolic health risk factors, including:

For an individual dealing with one or more of these issues, strategically implementing fasted running may improve blood sugar control, reduce insulin, reduce triglycerides, and improve body composition. (Source, Source)

Blood glucose and glycogen provide a significant fuel source during exercise; however, glucose and glycogen represent a limited “fuel tank” compared to fat inside the body. For reference, your body has only 1,800-2,000 calories in glycogen; by comparison, even a lean runner has nearly 100,000 calories of energy available from body fat! (Source)

Therefore, improving your body’s ability to use fat for fuel offers a distinct advantage. By burning more fat to fuel your runs, you can become less reliant on glucose, meaning you don’t need to eat as many carbohydrates during your run.

This next point is an extension of the point I just made above: Fasted running may increase your body’s ability to burn fat for fuel in general and enhance its ability to burn fat for fuel at higher running intensities.

For many years, fat was believed to only be a significant fuel source for running up to around 65% of your VO2 max. However, more recent research has flipped this notion on its head, showing that well-trained athletes can burn fat at much higher exercise intensities than previously believed. (Source, Source)

Research suggests that fasted endurance exercise may increase the number of mitochondria in your body.

Mitochondria are the “powerhouses” of your cells that make energy (adenosine triphosphate, or “ATP”) from the carbohydrates, fats, and (to a limited extent) the proteins you eat. Mitochondria also have numerous other functions inside your body, regulating everything from training adaptations to gene expression. (Source, Source)

Fasted training increases “mitochondrial mass,” or the quantity of mitochondria in your muscle cells. Increasing the mitochondrial mass of muscle cells means the muscle cells can make more energy to power your runs! (Source)

Running fasted can be convenient, especially for those of us who are crunched for time in the morning. However, for many runners, the downsides of fasted running, discussed next, far outweigh the convenience factor.

There are a variety of potential downsides to fasted running. Let’s discuss each of the downsides in turn.

Fasted training, especially fasted training at higher intensities, may raise cortisol, one of the body’s stress hormones. Sustained high cortisol levels can impair exercise recovery. It may take longer to recover if you regularly run in a fasted rather than a fed state.

Even though many athletes try fasted running to lose body fat, it may not work well for this purpose.

Research shows fasted cardio doesn’t lead to more fat loss than non-fasted cardio. A study compared fasted vs. non-fasted cardio while also reducing subjects’ calorie intake. The subjects did lose weight; however, because there was no difference in weight loss between the fasted vs. non-fasted cardio groups, the driving factor behind the weight loss appears to be calorie restriction, not fasted cardio. (Source)

A comprehensive review article also found no significant change in fat loss or body fat percentage in people who performed fasted overnight exercise. (Source)

Furthermore, in some people (especially women), fasted exercise may promote body fat gain!

Fasted exercise triggers an acute increase in cortisol, your body’s primary stress hormone. A sharp rise in cortisol is a normal response to this type of training. However, chronically elevated cortisol from ongoing stressors such as frequent fasted running can wreak havoc, including promoting body fat gain.

Chronically elevated cortisol has many downsides – impaired exercise recovery (mentioned above) and disrupted female hormones and testosterone in men (discussed below) among them. However, one of the common signs of chronically elevated cortisol is increased body fat, especially around one’s midsection.

Women’s bodies, especially premenopausal women, are highly sensitive to calorie insufficiency. Fasted running induces an acute calorie deficiency, which may manifest as declines in estrogen and progesterone (both of which are necessary for many aspects of female health and the menstrual cycle) and possibly as amenorrhea, the loss of one’s menstrual cycle.

By causing chronically elevated cortisol, chronic fasted running could lower testosterone in men. This could result in a loss of muscle mass, difficulty building muscle mass, and a low libido, among other effects. (Source)

In susceptible individuals, fasted running may be a slippery slope into disordered eating behaviors or relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S).

Please note that I specifically said “susceptible individuals;” not everyone who runs in a fasted state 1-2 times a week is going to develop an unhealthy relationship with food or an eating disorder.

This is one of the qualms I have with sports nutritionists who are dead-set against fasted training, claiming it causes eating disorders. This simply isn’t true; many other factors must be in place for an eating disorder to develop, including poor body image, depression or anxiety, and a perfectionistic personality, just to name a few.

Fasting during a long run of 3-4+ hours may cause your body to break down your muscles for fuel. As your muscles are broken down, the amino acids that are released can be converted into glucose through a process called “gluconeogenesis.” (Source)

Most runners want to build or maintain their muscles, not lose them! If building muscle is important to you, fasted running may work against your goals.

Fasting is inappropriate before high-intensity runs, such as interval or sprint workouts. These types of runs are glycolytic, meaning they require glucose as the primary fuel source.

If your glycogen stores are depleted, and blood glucose is low due to fasting before this type of running workout, you’re likely to feel VERY flat and fatigued. This is why I only recommend strategic fasted training during Zone 1 and 2 running, which are lower exercise intensities that can be fueled effectively by fat.

Some sports nutritionists argue that fasted exercise should NEVER be undertaken. I prefer to recognize the nuances in nutrition guidelines and do not make blanket statements. Some athletes benefit from fasted running, and some should stay away from it entirely; it depends on the individual and his or her health status and training goals, among other factors.

Here are some key considerations for running fasted:

There are many people for whom fasted running is NOT appropriate, including:

If fasted running is appropriate for you and you desire to incorporate it into your routine, there are several strategies you should implement for safe and effective fasted running:

Fasted running is a nuanced topic. There are multiple potential pros and a handful of potential cons; it is crucial to

If you need clarification on whether fasted running is right for you, or are interested in trying it but need help with implementation, a sports nutritionist can help! In my sports nutrition practice, I regularly help my active clients navigate nutrition strategies such as fasted running safely and effectively.

Do you want to optimize your nutrition so you can reach the next level with your athletic performance? I can help! Book a complimentary discovery call with me to learn about my sports nutrition services and how I can help you!

The content provided on this nutrition blog is intended for informational and educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it because of something you have read on this blog.

The information and recommendations presented here are based on general nutrition principles and may not be suitable for everyone. Individual dietary needs and health concerns vary, and what works for one person may not be appropriate for another.

I make every effort to provide accurate and up-to-date information, but the field of nutrition is constantly evolving, and new research may impact dietary recommendations. Therefore, I cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information presented on this blog.

If you have specific dietary or health concerns, please consult a qualified nutritionist or another healthcare professional for personalized guidance.

I empower others through nutrition to conquer their mountain adventures, drawing from my own experiences.

With a background in Biomedical Science and an M.S. in Human Nutrition, I’m a Certified Nutrition Specialist and Licensed Dietitian Nutritionist. My journey in functional medicine has equipped me to work alongside athletes and tackle complex health cases. As a passionate trail runner, backcountry skier, and backpacker, I strive to support others on their paths to peak performance and well-being.

Sign up for updates that come right to your inbox.

Kim says:

Thank you–this was so helpful! I’m a post-menopausal woman who runs fasted most days because of convenience. I also carry a couple of extra pounds around my midsection that I haven’t been able to get rid of since the major hormonal change. I’ve suspected cortisol was the culprit, but I didn’t really understand why! I really appreciate your detailed explanation!

Lindsay Christensen, MS, CNS, LDN says:

Hi Kim, thank you for your feedback! I’m so glad you found my article helpful!